I was 15 years old, expressing my views rather loudly as normal at my youth group.

That week I had been skateboarding on Nottingham city centre’s Market Square with my friends as usual. Two policemen had approached our group and informed us that we were not allowed to skateboard here, and if we continued, our boards would be confiscated. I told the policeman I would stop skateboarding if he told the mountain bikers across the other side of the square to stop cycling. He told me it ‘wasn’t the same’ and refused to continue the conversation.

Later that day we went to a church car park, only to be greeted by a big sign saying ‘no skateboarders’. Not even ‘no skateboarding’, but ‘no skateboarders’. I was really angry. More than just a little bit angry. It wasn’t about not being able to skateboard where I wanted, it was about people’s attitudes and prejudice towards skaters, towards young people who were ‘a bit different’, it was about people’s irrational fear of subcultures. It was about a church that was supposed to love young people, but instead put up signs to keep them away.

Later that day we went to a church car park, only to be greeted by a big sign saying ‘no skateboarders’. Not even ‘no skateboarding’, but ‘no skateboarders’. I was really angry. More than just a little bit angry. It wasn’t about not being able to skateboard where I wanted, it was about people’s attitudes and prejudice towards skaters, towards young people who were ‘a bit different’, it was about people’s irrational fear of subcultures. It was about a church that was supposed to love young people, but instead put up signs to keep them away.

My rant became a preach, as I told my friends about the Jesus I knew, who didn’t just love subcultures and marginalized people, but who actually made a conscious and deliberate effort to seek out those people. The Jesus who stepped into peoples boats, who went to all the places no one would go, who got into trouble because of who he hung out with and what he said.

Then came the idea.

A project, run by Christians, not just to include subcultures, but to actually work with them.

It was a great idea. But I couldn’t do it. You see I wasn’t good enough. I was one those ‘annoying’ kids in the youth group. The one who did lots of stupid things and distracted others, the one who questioned everything, the one who was always too honest, about everything. The one who had been through a lot of bad stuff. The one who the youth workers breathed a sigh of relief about when I didn’t show up.

Two years passed, and I was half way through A levels I was failing. My tutor suggested I explored other avenues, my teachers said I wouldn’t amount to anything because I couldn’t focus and apply myself. I had to leave, or they would have made me leave. Which to be honest, was fair enough. Most of the time I turned up stoned, and when I was there I was arrogant, distracting and sarcastic. I lived a double life of being a Christian who went to church on Sundays, but failed miserably to put anything I believed into practice during the week.

Suddenly, glandular fever hit. All I could do was lie in bed and think. I thought about me, I thought about God, I thought about my life. I thought about where I was headed. And I thought about that day, at youth group, about that idea. I thought about those skaters, on the market square, rejected by the church. And I knew I had to make my choice.

I left Nottingham at 17 to take a gap year with the only organisation who accepted year out volunteers under 18 with no money. I was placed with a church, and a Youth for Christ centre. Within six weeks I knew youth work was my calling. I gave up skateboarding, but skateboarders remained burned on my heart. I couldn’t avoid them. I kept thinking about that idea. Someone should do that I thought. But not me, because people like me don’t do stuff like that. I’m not good enough.

I did a second gap year, and during my second year, the national director of Youth for Christ at the time, Roy Crowne, came to speak at an event in our city. We had dinner with him, and I told him about my idea. I got excited as he thought it was good, and said ‘you should do it’. He asked me whether I’d ever written my idea down.

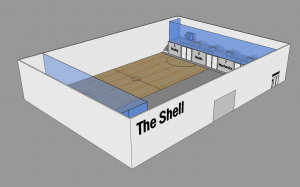

That night I poured my heart out onto a piece of A4. The project would be called ‘One Eighty’. It would provide young people with great skate facilities, but most importantly, it would allow young people the opportunity to turn their lives around, to change their minds, to move from a life without God to a life with God, to ‘One Eighty’.

That night as I slept, I dreamt of a skate event, that I was running.

I saw a set of double doors, with glass windows.

Beyond the glass windows was a massive group of skaters, queuing down some steps, onto the road, waiting to get in. To this skate event, to the first ever ‘One Eighty’.

The next day I marched into the venue and told Roy about the idea. I expected him to take my idea and make it happen, but what he said in response definitely surprised me. He vaguely glanced at the piece of paper I had spent nearly all night working on. And he just said one sentence, and walked off, which I will never forget. “You better get on with it then. Because if you don’t do it, then no one will”.

I had another choice to make.

More time passed, and now I was nineteen years old. I had arrived for my first day at work at Bath Youth for Christ, as their new ‘Skate Outreach Worker’. My job was to turn this idea into reality, to make One Eighty happen, as my placement as part of my youth work degree. I had no qualifications. I was a teenager. I still wasn’t very good at being a Christian during the week. All I had was a desk, and a chair. That was it. No money, no team, no resources, nothing. A broken, unqualified, insecure, lonely teenager, full of pain and questions and anger and fear.

I did a survey of local skaters, to find out their views and needs. I spent time at the skate park getting to know people. I introduced myself at the skate shops. I wrote a business plan. I worked out how much money we would need. There was a lot of zeros. I told the trustees what I wanted to do. They were amazing, and were up for giving it a go. We agreed to hold a test event, where we could try the ramps we wanted to buy, and see whether the need was really there. If there were more than 100 people, then we would go ahead and launch One Eighty as a project.

The launch event date arrived. We had a great venue, we had the ramps hired, we had the volunteers, we had a logo, we had the press coming, we had a great DJ, we had the local skate team coming to give a demo, we had everything. One hour until we opened, and everything went wrong. The DJ was stuck in traffic, the people bringing the ramps were lost, I had forgotten about five hundred things. Half an hour to go and everything arrived, we just about got it all up and running in time.

Five minutes to go and I remembered that I hadn’t put up the signs on the front door. We hadn’t arrived through the front door where the young people would be arriving, we had entered with the equipment through a side door. I walked very quickly with the signs in my hand, and as I approached the entrance my heart leaped out of my chest, and I dropped the signs on the floor.

I saw a set of double doors, with glass windows.

Beyond the glass windows was a massive group of skaters, queuing down some steps, onto the road, waiting to get in. To this skate event, to the first ever ‘One Eighty’.

My dream just came true. That had never happened before. We saw 400 young people come through the door that day. It was absolute chaos. I loved every second of it. I wasn’t sure, but I think there was a need for a skate project. I think there was a need for ‘One Eighty’.

Later that day we went to a church car park, only to be greeted by a big sign saying ‘no skateboarders’. Not even ‘no skateboarding’, but ‘no skateboarders’. I was really angry. More than just a little bit angry. It wasn’t about not being able to skateboard where I wanted, it was about people’s attitudes and prejudice towards skaters, towards young people who were ‘a bit different’, it was about people’s irrational fear of subcultures. It was about a church that was supposed to love young people, but instead put up signs to keep them away.

Later that day we went to a church car park, only to be greeted by a big sign saying ‘no skateboarders’. Not even ‘no skateboarding’, but ‘no skateboarders’. I was really angry. More than just a little bit angry. It wasn’t about not being able to skateboard where I wanted, it was about people’s attitudes and prejudice towards skaters, towards young people who were ‘a bit different’, it was about people’s irrational fear of subcultures. It was about a church that was supposed to love young people, but instead put up signs to keep them away.